Just a year ago, higher education was ensnared in what was then believed to be its greatest reputational crisis in modern memory. Varsity Blues was, in the words of critics, “an existential crisis” for a sector that had already been facing mounting disapproval from the American public for high costs and questionable value.

Fast forward a year. Varsity Blues feels positively manageable when compared to the trial facing higher education today. Higher education is indeed fighting for its license to continue to operate in a Covid-infected world.

The challenge needs little rehashing. Stripped of the ability to offer a four-year residential learning experience—where learning, living, and coming of age freely converge—the sector needs to redefine its value proposition.

The spadework of the spring and summer has been the detailed return-to-campus plans that have been assembled with thoughtful diligence and at whiplash speed, given the urgency of stakeholders’ need to know when, what, and where. The thinking applied to solving these issues was framed in hope of a flattened curve and a return to normal. It’s September, and neither has occurred and the higher education model is forced to reimagine its future.

For a sector that has clung to tradition and time-tested routines, the ability to reconfigure the rhythms of learning and living in such short order has been remarkable. The task ahead, however, is to unequivocally articulate its value proposition in the new landscape. While many reopening plans have strived to communicate this, the next four months will necessitate repeating it, demonstrating it and proving it.

On a deeper level, what this requires is transformation—not just to get through Covid-19, but for the long term. Nearly every industry is in the midst of some form of transformation; they have either been prompted by Covid-19 to begin a transformation that had been plotted or spurred to accelerate one already underway. Higher education cannot be the exception.

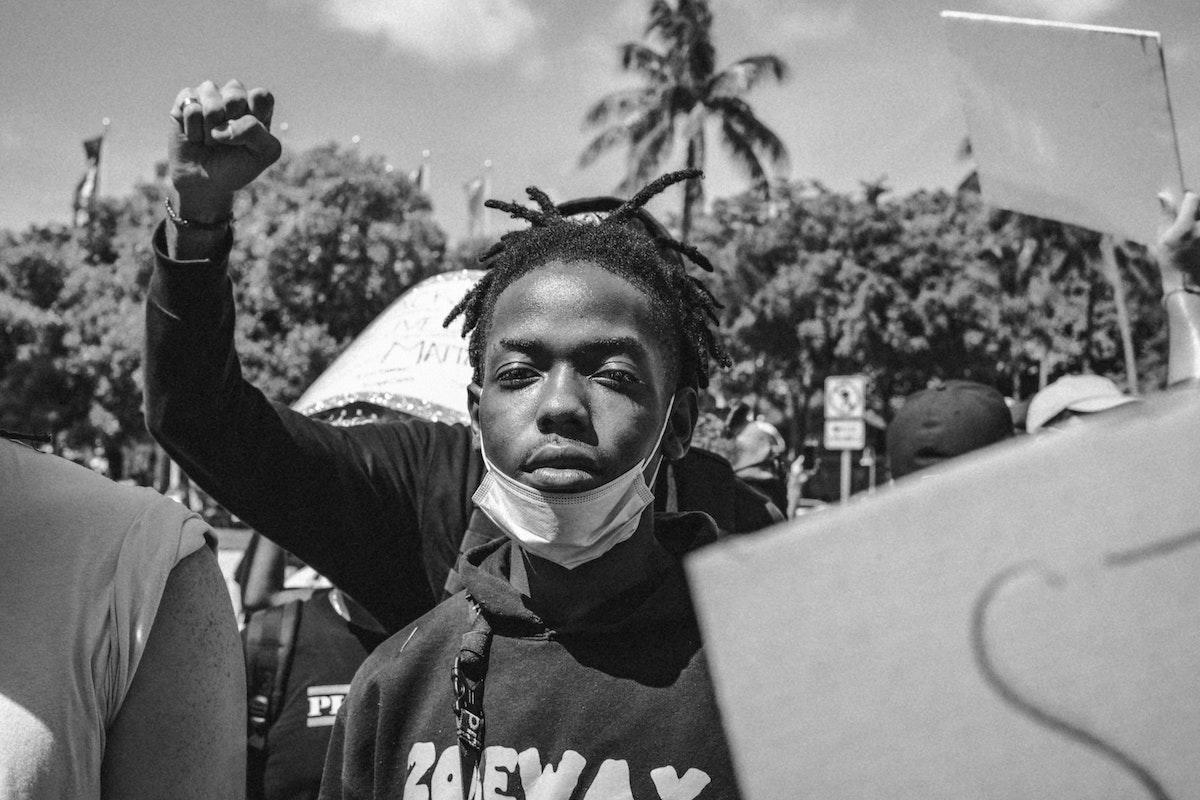

Well before Covid-19 hit, scrutiny over access, affordability, and value for the price of the degree plagued the sector. More recently in the wake of George Floyd, concerns over equity and diversity—in student bodies and among faculty—have grown significantly. And in an uncertain economy, the willingness of parents and students to pay premium prices for brand name education is no longer a given. These are issues that can no longer be pushed to the side.

As we grapple with the reality that everything will look different this fall, institutions should not hold their breaths and hope for a return to normal. Presidents and boards should seize the opportunity to lay out a broader vision for what they must deliver in the decade ahead, and how they will transform to get there. The higher education system today was developed in an analog world and even though it has incorporated digital technologies and new approaches to learning, the foundation of its culture, community, and operating structure must adapt to a new world with new demands.

Logistically, institutions should engage in intense listening, not simply to current students, parents, and faculty, but to those they will serve in the future. Only from this can institutions begin to develop the transformation roadmap, the operational changes, and the narratives to articulate them. Within the sector, this is also a time for deeper differentiation driven by a clear brand story. What is the role of the public university of 2020 and beyond? What is the specific value that parents and future students (who may be less brand-conscious than their predecessors) will derive from the private university of tomorrow?

This transformation will take time. But in the near term, higher education should signal that deep institutional change—going beyond dorm layouts and football seasons—is coming.

In tandem, and especially this fall, institutions need to rethink how they are engaging and communicating with students. With the built-in, physical community no longer a given, presidents and institutions can’t rely on letters alone to replace the high-touch engagement that many students have come to expect. Communicating often and meeting students where they are on the issues they care about will be more important than ever this fall. Preserving a sense of campus culture depends on it.

American higher education has long enjoyed a reputation for being among the best in class. This is a once-in-a-century moment to bring forward the best of what the sector has traditionally delivered, while creating a system that meets the practical needs of an irrevocably changed world and a reshaped higher ed customer. The sector is being tested and it will either pass or fail.

Kate Linkous is an Executive Vice President, Higher Education and Corporate Affairs.